Choreographed in Uniform Distress / Coreografiados en uniforme zozobra

- Jun 10, 2018

- 6 min read

MEET THE AUTHOR

MEET THE TRANSLATOR

ISAAC GOLDEMBERG nació en Chepén, Perú, en 1945 y reside en Nueva York desde 1964. Sus publicaciones mas recientes son Libro de reclamaciones (2018) y Philosophy and Other Fables (2016). En el 2001, su novela La vida a plazos de don Jacobo Lerner fue seleccionada por el Yiddish Book Center de Estados Unidos como una de las 100 obras más importantes de la literatura judía mundial de los últimos 150 años. Ha traducido la poesía de Donald Axinn, Stanley H. Barkan, Billy Collins, Peter Thabit Jones, Charles Simic y Aeronwy Thomas. De 1971 a 1986 fue catedrático de New York University y actualmente, es Profesor Distinguido de Humanidades en Hostos Community College de The City University of New York, donde dirige el Instituto de Escritores Latinoamericanos y la revista Hostos Review.

BOOK SUMMARY

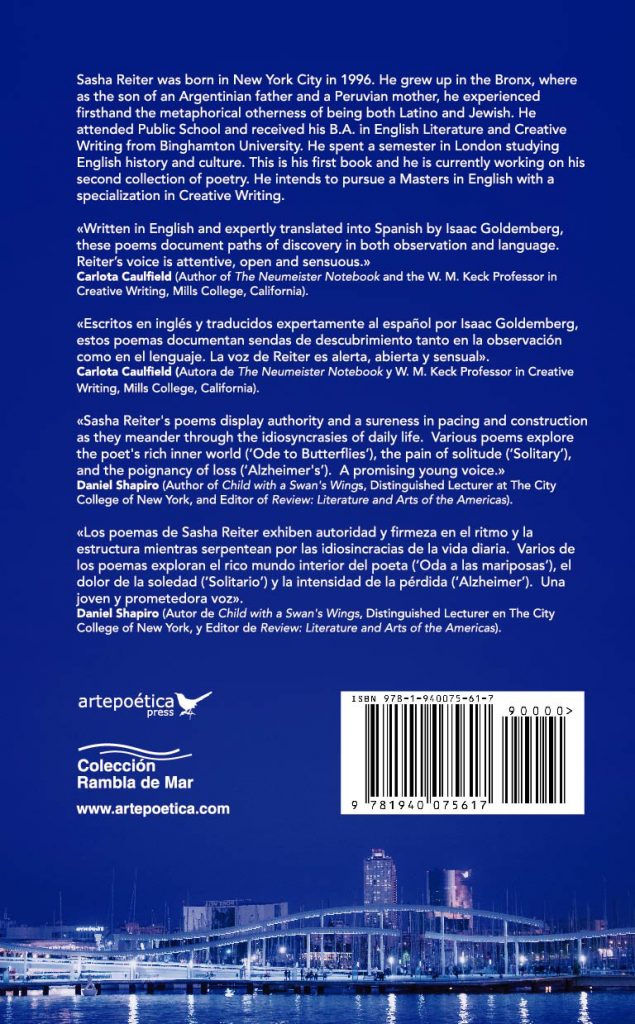

Sasha Reiter debuts with this bilingual poetry collection translated into Spanish by Isaac Goldemberg. Carlota Caulfield called his voice “attentive, open and sensuous.” Daniel Shapiro has called him “A promising young voice.”

Sasha Reiter debuta con esta colección bilingüe traducida al español por Isaac Goldemberg. Carlota Caulfield dice que su voz es “alerta, abierta y sensual”. Daniel Shapiro lo ha llamado “Una joven y prometedora voz”.

Comments